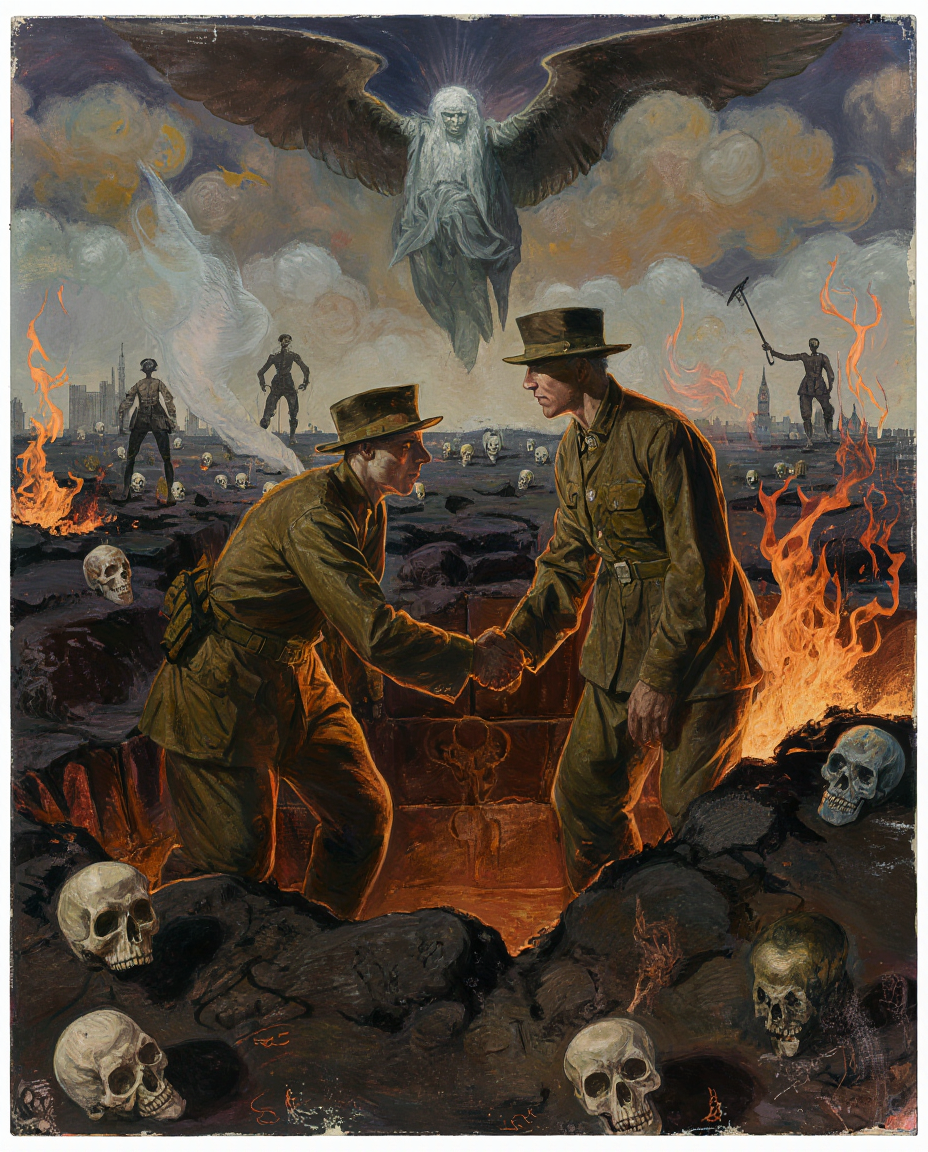

– by Wilfred Owen

1

It seemed that out of battle I escaped

Down some profound dull tunnel, long since scooped

Through granites which titanic wars had groined.

Yet also there encumbered sleepers groaned,

Too fast in thought or death to be bestirred.

Then, as I probed them, one sprang up, and stared

With piteous recognition in fixed eyes,

Lifting distressful hands, as if to bless.

And by his smile, I knew that sullen hall,—

By his dead smile I knew we stood in Hell.

Explanation

The speaker feels like he’s escaped from a battle and finds himself in a dark, creepy tunnel deep underground, carved out by ancient wars. It’s a grim place, like a grave, filled with sleeping or dead soldiers who can’t be woken up. As he looks around, one figure suddenly stands up, staring at him with sad, knowing eyes, almost like he’s trying to bless or comfort the speaker. The figure’s eerie, lifeless smile makes the speaker realize they’re in Hell—not a fiery one, but a cold, hopeless place. This sets up the poem’s surreal, dreamlike vibe, where the speaker is confronting the horrors of war in a strange, otherworldly setting.

2

With a thousand fears that vision’s face was grained;

Yet no blood reached there from the upper ground,

And no guns thumped, or down the flues made moan.

“Strange friend,” I said, “here is no cause to mourn.”

“No cause to mourn?” he answered, “None, save one:

The undone years, the hopelessness. Whatever hope

Was yours, or mine, was killed in this retreat.

The truth is known, only too late to speak.”

He spoke, and gazed, and I, too, felt like one

Whose laughter dies within a dream’s distress.

Explanation

The speaker is shaken by the figure’s face, marked by fear and pain, but notices there’s no blood or sounds of war down here—it’s eerily quiet. He tries to comfort the figure, saying there’s no reason to grieve in this place. But the figure disagrees, saying the real tragedy is the “undone years”—all the time and potential lost because of war. Both of them had hopes and dreams that were destroyed in this pointless fighting. The figure’s words hit the speaker hard, and he feels trapped in a nightmare where joy and hope can’t survive. It’s like they’re both mourning what war has taken from them.

3

“For by my glee might many men have laughed,

And of my weeping something had been left,

Which must die now. I mean the truth untold:

The pity of war, the pity war distilled.

Now men will go content with what we spoiled,

Or, discontent, boil bloody, and be spilled.

They will be swift with swiftness of the tigress.

None will break ranks, though nations trek from progress.

Courage was mine, and I had mystery;

Wisdom was mine, and I had mastery:

To miss the march of this retreating world

Into vain citadels that are not walled.

Explanation

The figure keeps talking, saying that if he had lived, his happiness could have inspired others, and his sorrow could have taught them something meaningful. But now, that’s all gone. He talks about “the pity of war”—the deep sadness of how war destroys lives and truths that should’ve been shared. He predicts that future generations will either accept the destruction war causes or fight back violently, but either way, they’ll lose sight of progress. The figure reflects on his own courage and wisdom, now wasted because he died in war, unable to contribute to a better world. It’s a powerful moment where he’s grieving not just for himself but for humanity’s lost potential.

4

“Then, when much blood had clogged their chariot-wheels,

I would go up and wash them from sweet wells,

Even with truths that lie too deep for taint.

I would have poured my spirit without stint

But not through wounds; not on the cess of war.

Foreheads of men have bled where no wounds were.

“I am the enemy you killed, my friend.

I knew you in this dark: for so you frowned

Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed.

I parried; but my hands were loath and cold.

Let us sleep now. . . .”

Explanation

The figure imagines a world where he could have cleaned up the mess of war with pure, deep truths, not by dying or fighting but by sharing his spirit freely. He laments that men suffer mentally and emotionally in war, even without physical wounds. Then comes the gut-punch: he reveals he’s the enemy soldier the speaker killed in battle. They were foes, but in this moment, they’re like friends, connected by their shared humanity. The figure remembers how the speaker killed him, and how he tried to defend himself but was too weak. The poem ends quietly with, “Let us sleep now,” suggesting they’re both ready to rest in death, united in their shared tragedy.

Difficult Words and Their Meanings

- Profound: Deep or intense, often in a serious or meaningful way. Here, it describes the tunnel as deeply dug or emotionally heavy.

- Groined: An architectural term meaning arched or vaulted, suggesting the tunnel was carved out like a cathedral by wars.

- Encumbered: Burdened or weighed down, referring to the soldiers who are stuck or trapped in sleep or death.

- Bestirred: Stirred or roused to action, meaning the soldiers couldn’t be woken up.

- Piteous: Deserving pity or sympathy, describing the figure’s sad, pleading expression.

- Sullen: Gloomy or grim, describing the depressing atmosphere of the tunnel/Hell.

- Grained: Marked or lined, here suggesting the figure’s face is etched with fear or pain.

- Flues: Channels or passages, used here to describe the tunnels carrying the sounds of war.

- Distilled: Purified or concentrated, referring to how war refines or reveals its own tragic pity.

- Citadels: Fortresses or strongholds, used metaphorically for unattainable or pointless goals.

- Stint: Limitation or restriction, meaning the figure would have given his spirit generously.

- Cess: A pit or filth, referring to the dirty, degrading nature of war.

- Loath: Unwilling or reluctant, describing the figure’s hesitation to fight back.

- Parried: Defended or blocked, as in deflecting a blow in combat.

No Responses